TALKS

Miho ODAKA + NATSOUMI

NATSOUMI :

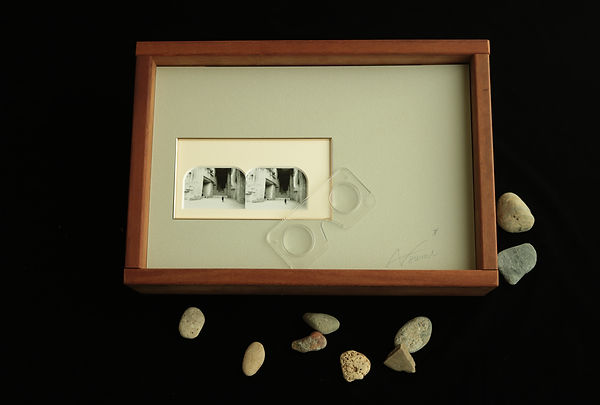

My name is NATSOUMI. I have always been fascinated by the invisible borders. Yet, it is unseen with the naked eye, and this is why photography fascinates me. I have published a photo book called "TOKΘYO ", a worldview that belongs to neither this world nor to the afterlife. What we announced at Sendai Month of Photography this time is what we call the stereograph, which is a kind of photographs that gives the audience a sense of three-dimensionality and depth when they see two subtly shifted photos separately with both their eyes. In Paris, where I used to live, there are many stereographs sold in flea markets. When I look at two photographs through the stereoscope (viewer), I feel as if I have crossed a specific border, and this sensation let me into the world of the photograph. I would like to express a sense of immersion and presence to the audience that would allow them to feel as if I have travelled back in time, so I decided to come up with a series.

Odaka:

I am Odaka, a photography curator. NATSOUMI's work this time focuses on the rather classical act of "seeing" through the stereoscope. By looking at the two-piece set of subtly shifted pictures with a stereoscope, one will realize that the photographs become superimposed as a single picture in their head. A stereograph reproduces a two-dimensional photograph with a three-dimensional effect and a sense of depth. Today, photos are available wherever you are. With computers or smartphones, one can still feel freshly excited with stereographs, and what is particularly attractive about stereographs is the fact that, when one looks at them through a stereoscope, people in the images would appear as if they were in a diorama. In a time when images are "shared," peeking into a stereoscope evokes a thrilling sensation in which one is trapped inside the theatre seeing the movie alone. The arched framing also creates a theatre-like impression. NATSOUMI, where did you take these photographs?

NATSOUMI :

These are photographs of my mother-in-law, who passed away two years ago, and when we travelled to southern France. Our family has been running a quarry for generations, and we decided to see this quarry near where we were staying after the landlady recommended that we go and give it a look. While the photographs are just a record of my mother-in-law, she was going deeper and deeper into the quarry. I was trying to catch up to her; I later realized that the quarry is actually where the French film director Jean Cocteau shot the purgatory scene in his movie Orpheus. The postmortem soul is purified and judged as it passes through this place that exists between this world and the postmortem world. In other words, as far as the movie is concerned, the quarry is the French version of "TOKΘYO". Looking at the photographs after the death of my mother-in-law, I felt the deepest sympathy. She had gone to a place like the film. What I found precious about photography is that, with each day passing by, you find yourself seeing more meaning in and feeling more intimate with them. My mother-in-law said many times in her sickbed that she had enjoyed the trip, and I felt like I wanted to turn the photographs into stereographs and show them to my father-in-law and husband.

Odaka :

The stereograph appeared shortly after the photograph came about, and people in Japan have started taking stereographs since the end of the Tokugawa era. I am personally fascinated by the stereograph. I have looked into various stereoscopes at photograph exhibitions thus far. I had also bought stereographs printed on albumen prints of the Taisho era at flea markets. The stereographs I bought were private photos. However, it's fascinating that NATSOUMI converts her journey into the small world of the stereoscope.

NATSOUMI :

Thank you. When my grandfather passed away, I found a heavy wooden box packed with lots of pre-war photographs taken when he was young. The photographs were wallet-sized. I remember being hit with this feeling of "fermentation" when I saw the pictures. Unfortunately, the pictures were put into my grandfather's coffin and burned. Still, having experienced what I had, for this particular photograph exhibition, I decided to frame the photographs to create this feeling of "fermentation".

Odaka :

NATSOUMI just mentioned the size of the photographs she had found being wallet-sized. I think size is a fundamental issue when it comes to the expression of photographs. In the past, people used to put photographs of their loved ones in pendants and wear them. Later, wallet-sized photographs became popular, and people started giving them away as gifts to those they were close with. I think that having a size that fits your hand increases your intimacy with the photograph as an object. There are many large-sized works these days and they all overflow visually, so I think that this exhibition is significant as it allows people to view the photographs one by one carefully. As symbolized by the word "fermentation," photos are seen by people could change its meaning with time. It is changeable with time and space. I heard that the definition of NATSOUMI's work had changed when her mother-in-law passed away, and, having listened to this, I once again felt that the essence of the photograph lies with the fact that it changes as if it were a living creature.

NATSOUMI :

The act of peeking alone into the stereoscope has to do with the concept of "intimacy" that Odaka mentioned earlier. Looking at someone else in the picture, it would make you feel as if you were doing that same thing as the subject, too. Large photos might be much less intimate because they are too powerful to face each other. How close the print is concerning oneself is what I found to be necessary. While we used transparent glasses, using a peep-through stereoscope would make one feel more intimate towards the photograph. Before this exhibition, we talked with a local optician, and he told us that, as is the case with glasses, where things look different depending on who wears them. So, too, are stereoscopes. He then suggested that I go with a general-purpose stereoscope that would allow as many people as possible to see through it under the same conditions. Different people walk away with varying impressions after seeing the same photograph, and I have learned that such physical differences also affect the act of "seeing". For this exhibition, we used stones and shells as captions for the titles of the works. Odaka, you like the stones too, don't you?

Odaka :

I love picking up random stones, following the rivers, the seas, and roadsides. Taking pictures is fundamentally identical to this action. Seeing values in random stones, "picking them up", and "selecting from them", is similar to "picking that right moment" when taking pictures.

NATSOUMI :

My five-year-old daughter likes to pick up stones and shells. When I asked the reason, she told me that they remind her of the day she picked them up; something pleasant to look back on. I suppose this is something that stones and shells have in common with photographs. A photograph is nothing but a piece of paper, but when you hold it in your hand, the feeling of the picture itself, the weather from when you take the picture, and what you talked about with people then – they all come back to you. I put photographs together with stones and shells for this particular exhibition because I wanted to show the audience that photos hold the same value as stones and shells. In the film "the Levistone from Castle in the Sky", the main character has a flying stone pendant. She inherits this jewel from her grand-mother. It is not only the support of a castle but also an identity of a family's lineage. I find the common factor between "the Levistone" and a photograph. I can't help but think how a photograph, which brings people back to the past ever readily, is just like the Levistone.

Odaka :

I find it interesting how you see the Levistone as a photograph. This reminds me of this project called "Omoïdé Sauvetage" that took place in Yamamoto, Miyagi Prefecture. It was a project where we washed clean photographs that had been washed away by the disastre on the 11 March 2011. The project aims to return the photos to the owners. This project had convinced me that photographs combine one's memories; photos have a kind of magic to bond family members and intimates. Having lost photos by the vigours tsunami, it might have deprived local people's identity and all their self-confidence. Some people could make up their childhood with their old photos. A photo is a piece of paper, but it's precious; it plays an integral part in one's self-confidence.

NATSOUMI :

French people have babies sleep on their several months after birth. In a French childcare book that I have read, it says that they show their babies pictures of their family members when putting their babies to sleep, which helps to calm down the babies. Showing photo-albums to put a baby to sleep, this night ritual inspired me. So do I with my daughter. The little girl fell asleep with ease with a photo of which she is with her father. Even a small child feels a secure attachment to a person in the picture, and the person is physically absent. It is the wallet-sized printed photos that remind us of not sympathy, but also intimacy with those who you love.

Odaka :

Before we go, would you be able to share with us what you have been up to recently?

NATSOUMI :

I live in Kakuda City. Upon a request from the city's Board of Education, I have been taking pictures in downtown. But also those who work there. I convert the images into stereographs. It is an archive project; the stereographs will be in safekeeping by 2040. the city's citizens like the treasure that they are. My daughter will have turned 25 then, and I just can't stop thinking about how she is going to react when she has seen her hometown through the stereoscope. This project will be meaningful but also significant. I'll do my best.

NATSOUMI

Photographer / Director of SOFA

NATSOUMI goes to France after graduating from Seijo University Faculty of Literature. After working as Katja Rahlwes's assistant, she studies at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle. The artist works as an assistant for children's workshops at the Louvre. After working as a magazine editor in the capital of France, she returns her home to Japan in 2010. "It is only with the heart that one can see rightly: what is essential is invisible to the eye" is her lifetime proposition, NATSOUMI has been making challenging works in the fields of visual arts and literary arts. Her photobook "TOKΘYO" has been well received at Ginza's Tsutaya Bookstore, and also at bookstores in Paris, Bordeaux, Leipzig, Berlin and Istanbul. Exhibitions at art galleries in Paris, NATSOUMI has also had multiple presentations held both in Japan and overseas. Next spring, her solo exhibition will be held at Ginza's Morioka Shoten in May 2020. NATSOUMI is currently working on non-camera photography workshops for children.